Why UK Farmers Protested Labour's Inheritance Tax Changes

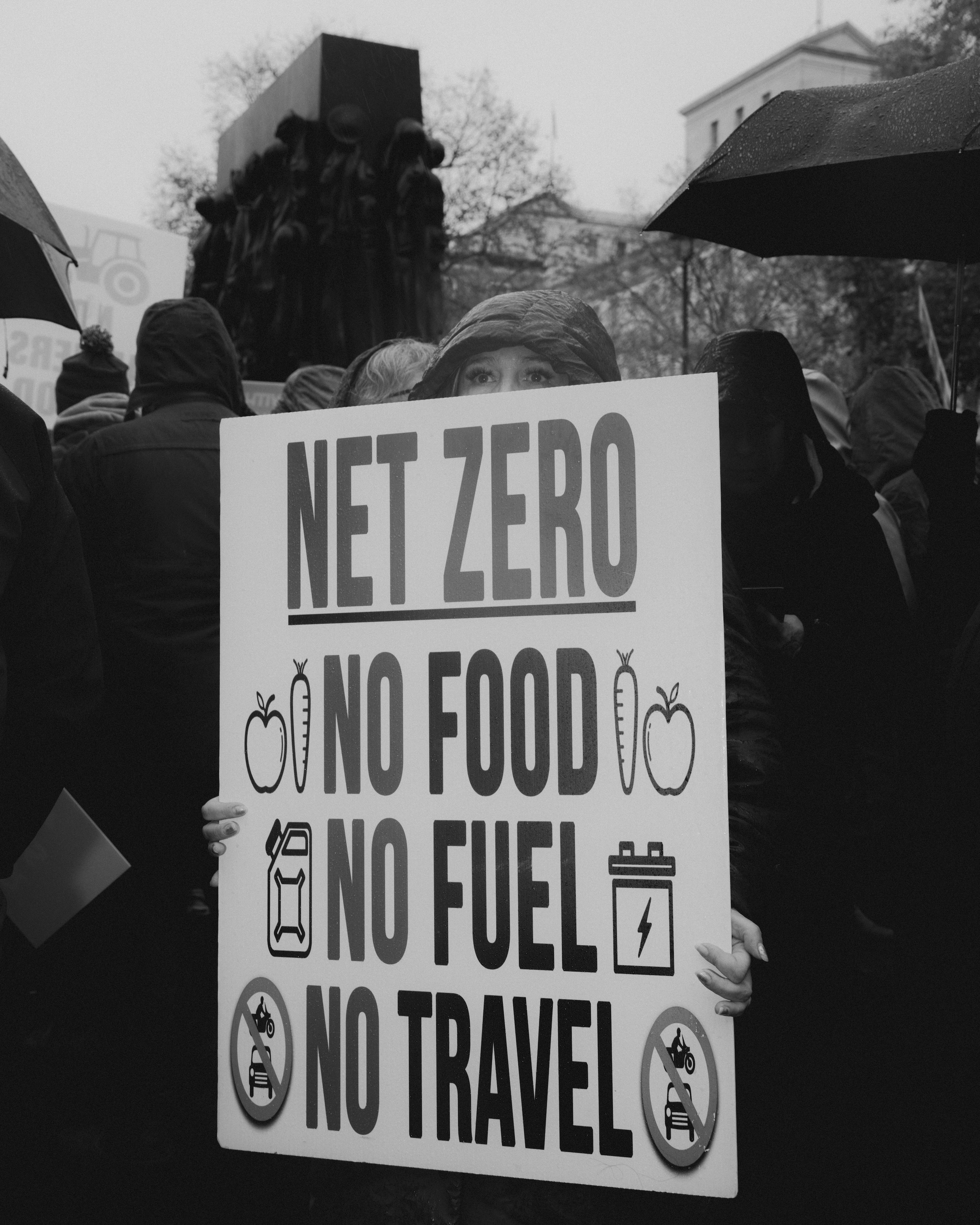

In November of 2024, farmers took to the streets of London to protest the Labour governments proposals to bring back inheritance tax on farms (at half the rate of regular inheritance tax, to be paid interest-free across ten years). Dan Burwood went out to capture the protest. Charlie Baker then pondered what all fuss is about.

Despite what many people claim, there is much to like about feudal Britain: the magnificent castles, the jutting great cathedrals, the heavy gold livery collars, the ermine robes, the homophonic melody of the lutes, the two-handed jewel-encrusted swords, the wastrel peers whose proclivities still pepper and season the tabloid press – there is, I think you will find, much in our medieval heritage that adds greatly to the gaiety of the nation.

But there is also, we can all admit, much to dislike about the manner in which the country is governed. Looking out over the vantage point of 2025, a quarter of a century into the new millennium, with the country in tedious and seemingly irreversible decline, it is wildly depressing to see how much attention, general goodwill and taxpayer booty is lavished upon farmers.

Yes, farmers, those wheat-chewing red-cheeked sorts you encounter outside the M25. The guardians of the countryside; the stewards of our rolling fields. They fill our families' mouths with the produce of their ceaseless toil. But they also occupy this bizarre role in neo-feudal Britain, where they believe themselves to be impervious to the rules and laws to which the rest of us must adhere.

By a generous calculation, farmers make up around 0.2 percent of the total population, yet their outsized influence on the body politic was vividly witnessed during the 'farming rally' in November last year, where more than 10,000 people descended on Westminster to protest against the Labour Budget, which promises to remove exemptions from inheritance tax for agricultural land. A small crowd, a relatively niche topic – but it dominated the headlines for days, with the slaughter of the Israel-Palestine war, the looming spectre of Vladimir Putin, and the incoming Trump presidency all demonstrably less important than maintaining the privilege of the rural upper-crust.

I told a friend that I was writing this article, and that it's a hard tone to strike, because it's such a vital subject, and I strive to not sound too worthy or too humourless. My friend lives in a trendy part of the West Country, and told me how their brother had bought a large house with 60 acres or so for a price of many millions some years back – you can probably guess what part of the country it is. The house has just a few fields for a horse, some gardens, a bit of parkland – and my friend's brother and his family have been able to exempt the house from inheritance tax by registering it all as 'agricultural land'. How did they do it? They just zhuzhed up one of the sheds, painted it a new colour and called it 'the farm office'. No business is conducted there.

Of course this sort of wheeze is well known to all the broadsheet columnists drowning their copy in hyperbole, claiming that the Starmer government – the bunch of slick north London lawyers that they are – had 'betrayed' the countryside, and that unless farmers could continue to enjoy their exemptions, that the population would, in time, starve. It is said that the media class don't 'understand' farmers, but, regrettably, I know them all too well.

Growing up in the vast food factory that is rural Lincolnshire, they were the ruling class. Not just jolly old yokels parpling along on tractors while sowing their fields of oats and barley; but business magnates with holdings of thousands of acres, cropping some of the most valuable agricultural land in Western Europe, shipping truck-loads of sugar beet to processing plants next to dual-carriage roads before distribution in articulated lorries beyond the county's borders. Fifth-generation potato barons; dog biscuit factory owners; UKIP activists; gangmaster-employers who shuttle Eastern European labourers to shiver in caravans next to the flat undulating fields.

It's not farming per se in The Fens, it's agribusiness. Eight miles south from my parents' house, at Carington, the eponymous hoover billionaire James Dyson has constructed a 26-acre glasshouse where 1,250 tonnes of strawberries are grown throughout the year, 'out of season', as it were. They're plucked by robots programmed to recognise when the fruit is ripe and juicy. It's an astonishing sight, security around the site is razor-tight, and only a select few are invited to witness the technological marvel of British strawberries grown in February.

Dyson, alongside the motormouth-hack-turned-international superstar that is Jeremy Clarkson, is one of the loudest voices of dissent against what is ridiculously billed as the 'family farm tax'. He has described the Budget as 'spiteful'. The Financial Times estimate that Dyson is on the hook for a putative inheritance tax bill of £120 million in 2026, which would be very handy for the Exchequer. Of course, the irony is that agricultural land has only been exempt from what the beancounters call 'IHT' since 1984, but such subtleties aren't to be endured.

Just look at Jeremy Clarkson's mottled neck vibrating in distress when a BBC journalist posed an impertinent question during the farming protests last year. It is, it goes without saying, amongst the blokiest of arenas – the grotty Barbours, tweed jackets, and mud-splattered boots are renowned almost to the point of cliché. By day, there is a governing starched formality: Viyella shirts, cords, and quarter-line zipped fleeces abound. Come the weekend, younger farmers wind down in a uniform of jeans, brogues, and Schoffel gilets over some lukewarm cans of John Smiths and a gin and tonic for 'her indoors'.

For here is an observation so obvious that it is almost not worth stating: farming politics runs the political compass from true blue Tory to foam-flecked reactionary. I had a front-row seat to the political upheaval that was Brexit: my local constituency of Boston and Skegness recorded the most enthusiastic vote for Leave across the United Kingdom: with over 74.9 percent voting to depart the European Union.

More profoundly, though, it is an industry that dislikes, if not despises, the young and the young-at-heart. I remember speaking to one farmer, a pretty sane man by and large; a veritable leftie by local standards. I suggested to him that he and other landowners in the area could club together and build a skate park in our local town, because that's the sort of thing that you have in most towns. He turned to me, purse-lipped, and said "No.They would just destroy it".

While there have been great creative minds in British agriculture – a tip of the cap to Thomas Coke – it is not a sector in which original thought is amply rewarded. It is, more often than not, a lonely and repetitive job. I had one good friend who was born into a serious farming family. His older brother, who was expected to take on responsibilities, but was academically gifted and went to university. He did not want to count out his twenties tilling the fields. My friend, then aged 16, was hooked out of school by his parents, and then spent the primest parts of his youth working two miles from the North Sea prison camp best known for having the now-un-disgraced novelist Jeremy Archer as an inmate. I remember, some years later, going to watch Newcastle play at St James' Park with him, and on the train to Grantham back, as we were passing Leeds and Nottingham, he started pounding Tinder on his iPhone; flick after flick to try and score matches as we zoomed past the cities where all the other 20-somethings were having fun and being normal.

There are many other such anecdotes that I could dredge up. But if I think of everyone around my age I grew up with – not just was chummy with – but actually knew, I think only two out of all of them still live in Lincolnshire, and the other one is a farmer, too. A whole county dredged of its young.

Of course, what happens in Lincolnshire with its Grade 1 agricultural land at £20,000 an acre is very different from what happens on a dairy farm in the Quantock Hills or a sheep-centred smallholding in the rain-lashed Lake District. But agricultural land has quadrupled in value in the last 40 years. The country is in dire financial straits and Jeremy Clarkson is carrying a megaphone outside Parliament Square and shouting that he doesn't want to pay tax. It is beyond satire, but the joke is entirely on us.

Charlie Baker is the Editor at The Fence magazine.