Rotterdam’s Aggressive Answer to Rave

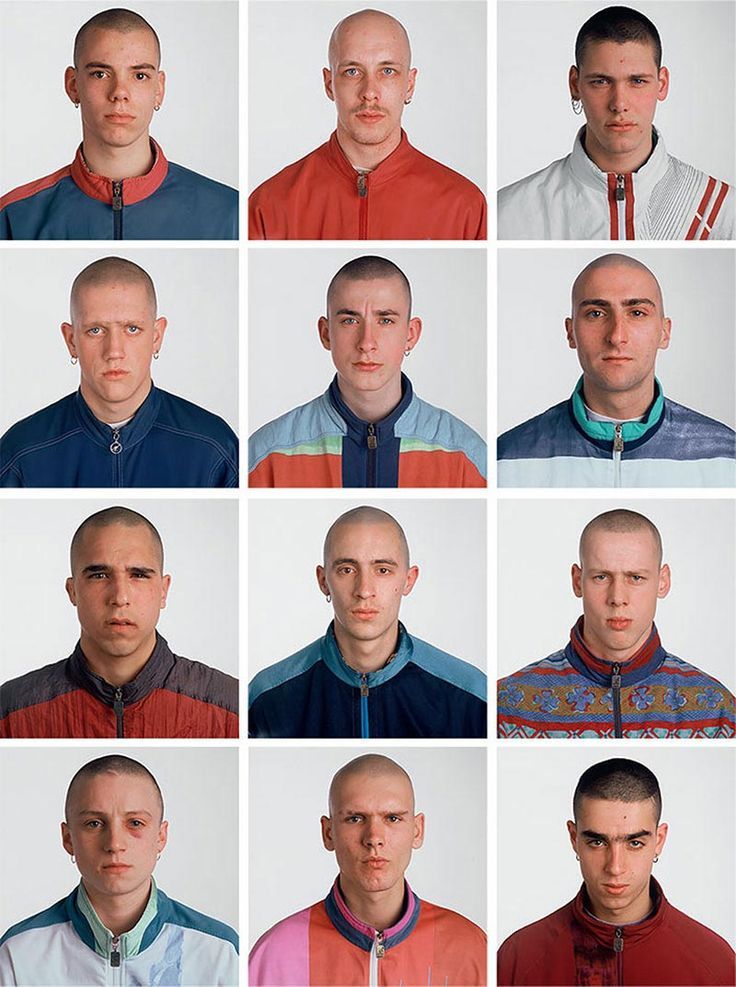

The kick drum doesn’t sound like music. It is too loud, too distorted, too fast to register as anything other than a rhythm. In a converted warehouse on the outskirts of Rotterdam, thousands of teenagers are stomping in time to it. Their heads are shaved, their tracksuits soaked through with sweat, and their Nike Air Max soles thud against the concrete floor in unison.

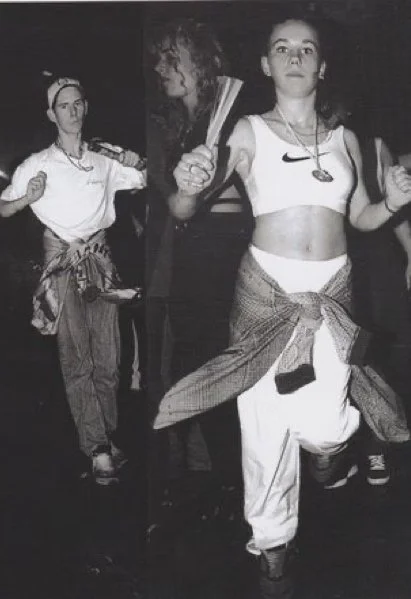

The dance is called Hakken. Legs piston up and down, arms jerk forward and back as if shadowboxing. Looks a bit like the floor is lava and you're trying to play a keyboard. The tempo is 180 beats per minute and rising. This is Gabber, a Dutch slang word for mate, and in the early 1990s it was the hardest, fastest, most uncompromising sound in Europe.

Gabber music was born in Rotterdam in the early 1990s. The city’s working-class youth took the skeleton of hardcore techno and stripped it of glamour. The result was raw, aggressive and defiantly unpolished.

The blueprint came from Frankfurt. In 1990, Mescalinum United’s We Have Arrived introduced the distorted 909 kick drum that would define gabber. Rotterdam DJs such as Paul Elstak, Rob Fabrie and the crew who would form Neophyte took that sound and pushed it further. They accelerated the tempo past 180 BPM, cut melodies down to skeletal riffs, and drenched everything in distortion.

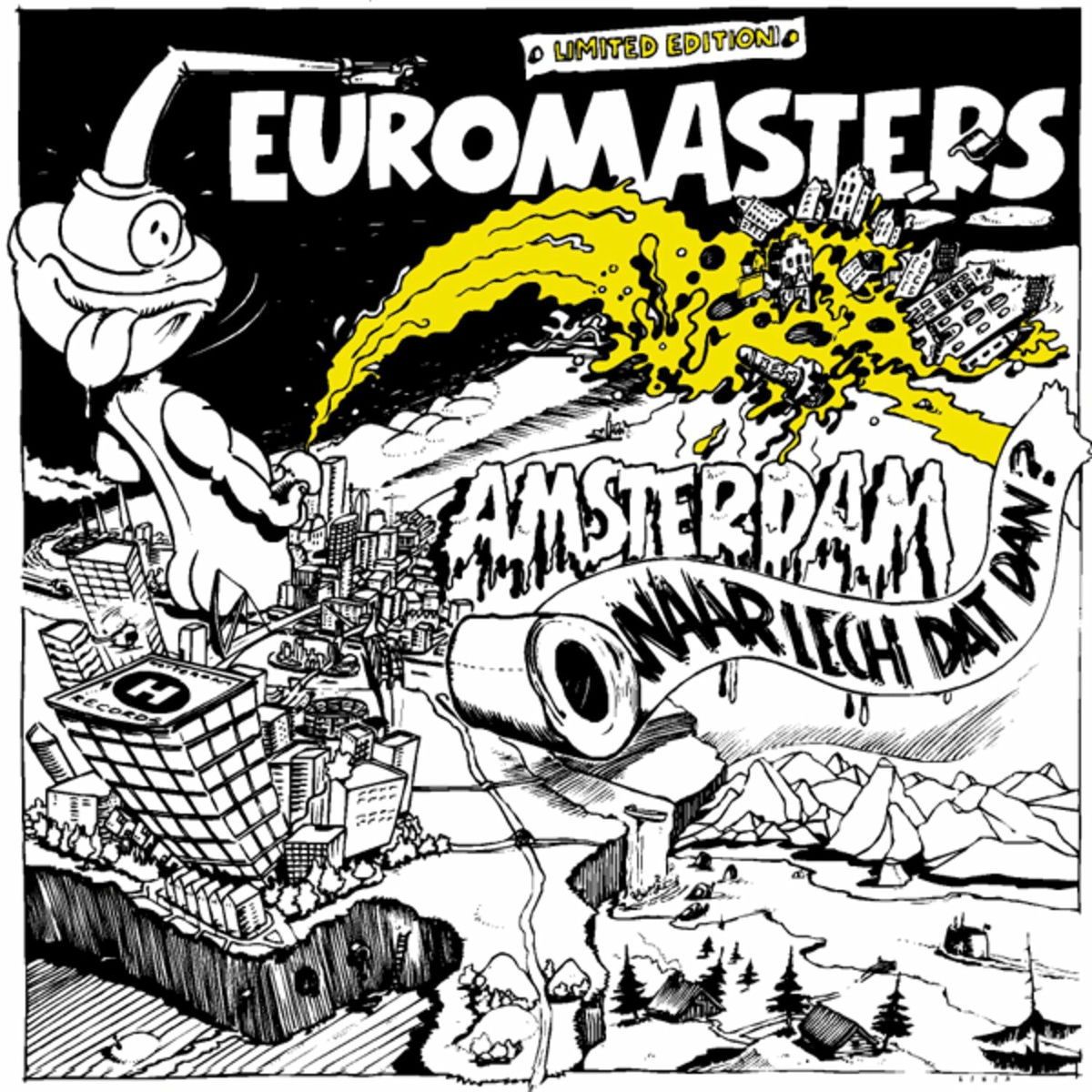

By 1992, Rotterdam Termination Source’s Poing turned a simple pinging synth into an unlikely hit, even breaking the UK Top 40. Human Resource’s Dominator, remixed in gabber style, became a global anthem and was even sampled by Lady Gaga. Rotterdam Records and Mokum Records pressed 12-inches that sold out instantly. ID&T launched the Thunderdome compilations (which I loved and my long suffering parents didn't) , with cartoon wizards and skulls on their covers. By the mid-1990s, Thunderdome CDs were shifting hundreds of thousands of copies, turning gabber from a local movement into a global subculture.

“We weren’t chasing respect. We wanted it harder, faster, more insane,” recalls Neophyte.

The rivalry between the two Dutch cities helped shape gabber. Amsterdam was cosmopolitan and fashionable, dominated by house clubs such as Multigroove. Rotterdam was a bombed-out port city defined by working-class grit. Feyenoord vs Ajax was already one of Europe’s fiercest football rivalries. Gabber became Rotterdam’s sonic counterpart to Ajax-dominated Amsterdam house.

For Rotterdam’s youth, playing gabber was a declaration of identity. This was not Amsterdam’s chic house music. It was Rotterdam noise. Loud, ugly, proud.

Where house culture was fuelled by MDMA’s warmth and empathy, gabber was driven by speed. Amphetamines were cheap and widely available in Rotterdam. They perfectly matched the music’s relentless pace.

A night at Parkzicht, the club that became gabber’s unofficial headquarters, was about stamina rather than subtlety. Six hours of hakke demanded chemical assistance. Crowds relied on pills and powders that sharpened focus and pushed bodies beyond their limits.

This gave the scene a jittery, aggressive edge. From the outside it looked threatening. From the inside it was release.

I think (!?), the world record for the fastest track ever made is Moby (yes the car advert guy) who produced a pastiche of Gabber called 'Thousand'. This track starts off relatively slow yet still quite aggressive and builds to a 1058bpm monster.

“People saw the shaved heads and thought hooligans. But most of us just wanted to stomp, get out the rage, and go home together,” says Arjen, a former gabber now in his forties.

Gabber was more than BPMs. It was an identity. Rotterdam’s working-class kids, often dismissed as louts by the Dutch press, found in gabber a culture that did not demand sophistication. The insult “stupid music for stupid people” became a badge of honour.

The look was strict. Shaved head. Australian tracksuit. Nike Air Max 90 or 95. The uniform blurred the line between rave and terrace firm. It terrified outsiders, which was the point, but inside it created belonging.

“The tracksuit and trainers made us a crew. You walked into a club and knew straight away who was gabber and who wasn’t,” remembers Martijn, who grew up in Rotterdam’s south.

Gabber was tied up with Rotterdam’s football identity. Feyenoord’s De Kuip stadium was a short walk from the same industrial zones where Parkzicht and other gabber venues thrived. Feyenoord’s support has always been fiercely working class, in contrast to Ajax’s reputation in Amsterdam. That rivalry carried over into nightlife.

The gabber uniform mirrored terrace style. Shaved heads and bomber jackets had already been adopted by hooligan firms across Europe. Adding an Australian tracksuit and a pair of Air Max 90s was enough to mark you as gabber rather than a football mob, but the line was thin. Both scenes were built on intimidation, loyalty and mateship forged on the edge of violence.

“On Saturdays you would be at the match, and that night you were at Parkzicht,” remembers Willem, a Feyenoord fan who grew up in the nineties. “It was the same lads. Sometimes the same fights, just in a different place.”

Terrace chants bled into gabber tracks. The aggression of the stands was channelled into hakke battles rather than scraps. In many ways, gabber was hooligan energy turned into dance culture. For kids in Rotterdam, it was a way to express the same defiance without ending up in a police van.

The connection between football and gabber also explains the strictness of the look. Just as terrace casuals used brands and trainers as code, gabbers used shaved heads and Air Max as shorthand. It was a way of saying who you were loyal to and where you belonged, whether on the terraces of De Kuip or the dancefloor of Thunderdome.

These records were more than dancefloor weapons. They were cultural markers for a generation of Dutch youth who felt ignored by the mainstream.

Gabber never conquered Britain the way jungle or garage did, but it seeped in through the cracks. Northern free parties and provincial warehouses in Doncaster, Blackpool and Stoke became outposts for Dutch imports.

The fit was natural. British nightlife has always had a soft spot for the over-the-top. From Oasis singalongs to donk, from football terraces to scouse house, the culture thrives on excess. Gabber slotted in as another form of too much.

“When we got Rotterdam records in Donny, it felt like we were hearing the future. It was ugly and brilliant, and it belonged to us,” recalls one veteran of the Yorkshire free party scene.

By the late 1990s, gabber collapsed under its own weight. The BPM wars reached absurd speeds, tracks became self-parody, and the wider public lost interest. Paul Elstak’s move into happy hardcore was seen as betrayal, while the harder edges splintered into terrorcore and speedcore.

But gabber did not die. Angerfist emerged in the early 2000s as the masked face of modern hardcore, keeping the distorted kick alive. Elements of gabber seeped into donk, hardstyle and later industrial techno. Even hyperpop owes something to gabber’s cartoonish aggression.

In 2008, Belgian duo Soulwax turned their cameras on gabber kids in Radio Soulwax. The video features slowed down Gabber tracks and overlaid original ravers showing the intricacies of the Gabber dance

It reframed gabber for a new generation, showing it not as menace but as suburban ritual. Those kids became precursors to the TikTok stompers of today.