Last year the fashion world was saddened at the passing of the legendary, incomparable Giorgio Armani. Here – with exclusive imagery from the Armani collection – writer Alex Bilmes looks back at his legacy.

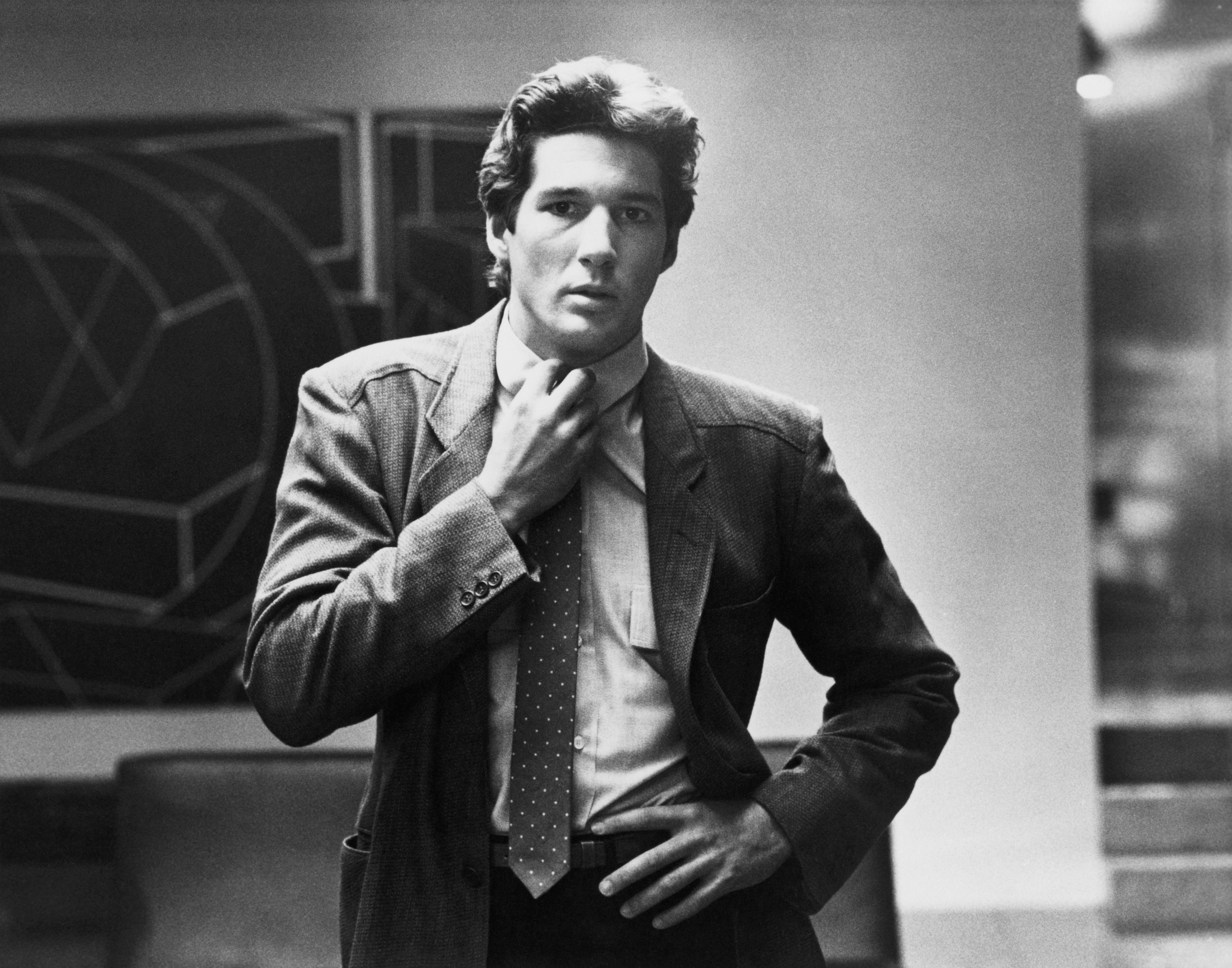

Principal photography on Paramount Pictures’ American Gigolo began in February 1979, at locations in and around Beverly Hills, California. The director was Paul Schrader, laureate of wounded masculinity, writer of Taxi Driver. The producer was a pushy up-and-comer called Jerry Bruckheimer. The soundtrack was by the disco visionary Giorgio Moroder, with help from Debbie Harry. The leading man was a 29-year-old actor from Philadelphia, luxuriant in his beauty – Richard Gere, not yet a major star, stepping late in the day into the loafers of John Travolta, who had accepted the title role but then changed his mind.

But the man whose work on the movie would leave the most enduring legacy, the reason American Gigolo is still talked of in awed whispers by aficionados of men’s style, was a 44-year-old Italian fashion designer only that year entering the American market: Giorgio Armani.

None of those associated with American Gigolo could have known it in 1979, but eleven months ahead of schedule the 1980s had arrived. Schrader and his cast and crew (tip of the hat to production designer Fernandino Scarfiotti), and especially his costume designer, had invented the look of the future, and to some extent its ethos and attitude: a world of hard surfaces and soft power, status and money, shopping and fucking. The Designer Decade.

The clothes Giorgio Armani made for Gere point the way. The go-go chest-rug flamboyance of the 1970s is gone, leaving only traces – a slight boot-cut flare to high-waited jeans, an extra button undone on a shirt. In its place, a thin-lapelled, slouch-shouldered, understated elegance. A muted palette, a flattering cut, a quiet confidence.

The novelist Bret Easton Ellis saw American Gigolo in the month of its release, February 1980. He was 15. In his essay collection, White, from 2019, Ellis describes how Gere’s appearance in American Gigolo “changed how we look at and objectify men.” The teenaged Ellis was witnessing the birth of what would later be called the metrosexual. The beginning, too, of a boom in men’s fashion and style, with which Giorgio Armani remains synonymous.

As the enigmatic Julian, a high-class prostitute framed for murder, Gere moves with a dancer’s grace, lithe and athletic, gliding through a nightmare as if it were a dream. He drives a black Mercedes 450 SL. He dangles from gravity boots in his silk boxer shorts, working his lats while simultaneously practising his Swedish. (Seriously.) He has refined tastes in art, in interiors. He is clearly excellent at shagging. So excellent, you’ll believe that Lauren Hutton – Lauren Hutton! – might consider paying for it.

“Cool, detached, and creepy,” is how David Thomson, the great lexicographer of cinema, describes Julian, in his own book, Sleeping With Strangers.

Elegance is how you wear something. Not how it wears you

He’s not wrong.

So what is it about Julian, this cipher, this poseur, that makes him so alluring?

It’s the clothes, bro.

That’s what makes men want to be him – and/or to have him. And, if we can’t be him or have him, then we can at least borrow his look. Giorgio Armani’s tailoring – light, flowing, classic, restrained – makes a man, any man, feel like they might be, just for a moment, what Julian is: a sex object. A style icon. A stud.

I would not, typically, use those words to describe myself – and neither would anyone else, worse luck. And yet…

I own a black silk blazer, ten years old, unstructured, thin as a tissue paper, light as a dollar bill, but somehow hardy as reinforced steel. I have battered this jacket on hundreds of sweaty summer nights on multiple continents, in situations formal and very much not so. I have scrunched it into suitcases, filled its pockets with cigarettes and God knows what else, spilled drinks on it, and still it hangs on me like I bought it off the rail the day before yesterday.

Giorgio Armani didn’t invent silk blazers, or any of the standards of the menswear uniform. He didn’t invent the modern men’s suit. What he did, in the 1970s and beyond, is transform it, ripping the stuffing out of the jacket to create a garment that was looser, more relaxed. Now tailoring could be lived in, moved in. Now stylish professional men, like Richard Gere’s Julian, need no longer feel stiffly buttoned up.

I have in front of me Giorgio Armani’s illustrated biography, published by Rizzoli; a survey of his life and work.

There are family photos and BTS shots from the shows, and many, many A-list actors modelling looks, but the images that stand out most are from the advertising campaigns.

A Peter Lindbergh photo from S/S 1993, for Giorgio Armani Eyewear, of a square-jawed hunk with a thick head of hair pushed back from his finely creased brow. Three fresh-faced junior financiers gussied up for the big time, by Craig McDean for A/W 2013-14. A father and son, almost sepia in tone, dad in a sweeping balmacaan overcoat, for Emporio Armani A/W 1983-84, by Aldo Fallai. A Brylcreemed city slicker in thoughtful pose from S/S 1997, by Paolo Roversi.

There’s sexier stuff, too. A shirtless Cristiano Ronaldo, sprayed with water, by Mert and Marcus, from 2010. A blond-cropped David James, the then-Liverpool goalkeeper, shot by Norman Watson in 1996, naked in a sprinter’s crouch. A himbo in tight jeans cradling a tiger cub under one arm, by Aldo Fallai from 1981. (None of your pale and emaciated wraiths at Giorgio Armani, thanks very much.)

It's the extraordinary consistency that strikes you most forcibly. Not that Armani didn’t develop his ideas as the years and decades flowed by, but throughout he remained faithful to his vision of sensuous masculinity: strong men in soft clothes. Chiselled torsos and bulging biceps, yes, but also a certain brooding sensitivity, even vulnerability. Stunning, but somehow accessible. It’s why you can wear Armani in the boardroom and the bedroom, but you can also wear it to the pub, to the football, to the gym – Armani imagery very much encourages trips to the gym – all the while feeling just a little bit smarter than the next guy.

It’s why you can wear Armani in the boardroom and the bedroom, but you can also wear it to the pub, to the football, to the gym

(In my late teens, with no hope at that time of ever being able to afford a Giorgio Armani suit, I bought a pair of Emporio Armani jeans, with the little gold eagle on the back pocket. My entrée to a world of style, sophistication, and fantasy.)

“My purpose in fashion,” Armani wrote, “is to offer a less severe, less rigid allure to the male figure… all the while preserving elegance and distinction and the idea that others should notice you for your mind and your self-esteem.”

Elegance is a word he uses a lot. What did he mean by it, I once asked him? “Elegance doesn’t mean to have to wear a jacket or a suit or to have a pocket square. It means the way you wear something. The way you hold yourself. Your gestures. This is where you can see someone’s character. It’s how you wear something. Not how it wears you.”

Throughout he remained faithful to his vision of sensuous masculinity: strong men in soft clothes

As you doubtless know already, Giorgio Armani died in September, in Milan, at the age of 91. The best way to remember the man who might be the most influential menswear designer who ever lived? To honour his legacy, and to appreciate the depth of his achievement?

Get hold of something – anything – he designed: a suit, if you can spring for it, or a shirt, or a pair of Emporio Armani jeans. Put them on. And feel, for a moment, that you are at the wheel of a black Mercedes convertible, cruising the Pacific Coast Highway, “Call Me” on the stereo, Santa Ana wind in your hair, the past in your rear view mirror, the future just around the next bend.