Since the release of 2001’s Goodbye Charlie Bright Nick Love has been at the very forefront of British masculinity. The director sat down with Sir! editor-in-chief Elgar Johnson and started from the very beginning.

ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE

The Football Factory changed my life. Sounds dramatic? Possibly. But I do specifically remember watching that film with my mates on DVD and immediately thinking that it would go on to have a massive impact in my life. The style, the realness, the casting – it felt like something me and my friends could relate to. The soundtrack just added to the experience: ‘Miss Lucifer’ by Primal Scream, ‘What a Waster’ by The Libertines, and the song that made boys act like they were about to lose their heads, David Guetta’s ‘Just a Little More Love (Wally López Remix)’.

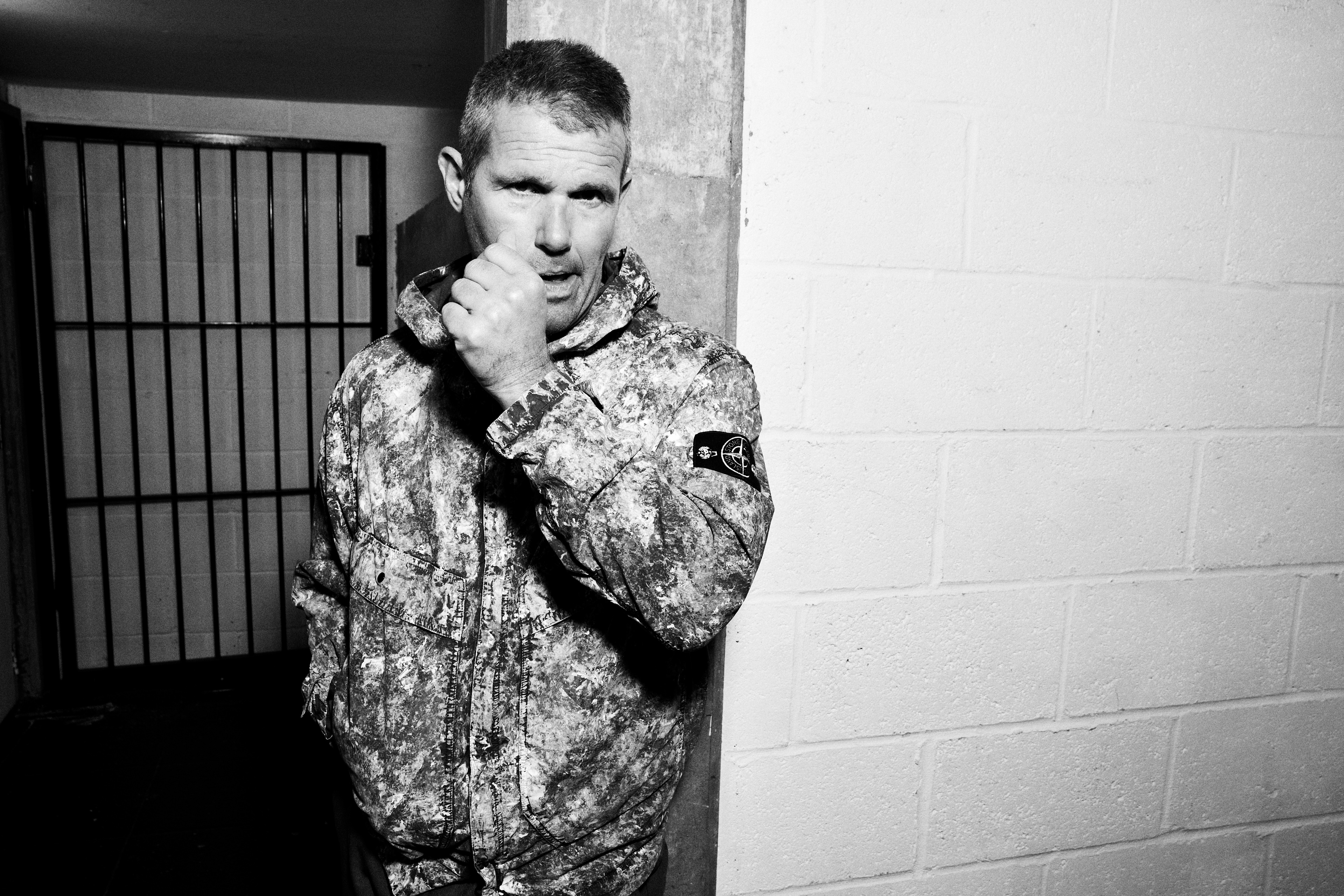

The film’s creator – and the architect of a whole movement – is British director Nick Love. They say never meet your heroes. I don't agree – to my detriment occasionally, as I’ve been burnt in the past. But not on this occasion. Nick is sitting in the brightest of orange jumpers when we meet, and instantly we’re discussing the Sir! cover shoot, and how he – quite rightly – should feature in the Stone Island campaign. He’d be completely at home with this, having been one of the faces of the early 90s as a male model. "So basically, what happened was me and Scott [Maslen], who's now on EastEnders, grew up about a mile away from each other in south east London,” Nick tells me. “But we never met each other. When I was a kid I used to get called Scott in the street – I'd turn around and go, ‘fuck off, it's not Scott’.” Eventually, some mutual friends put them in contact. “It turned out he’d spent most of his life being called Nick by random people.”

The pair travelled to America, and after managing to acquire a grand (“Scott nicked £600 from his work, and I nicked £400 quid from somewhere else”) flew to Miami in 1990. “What we didn't realize was it was right at the end of the Cuban crime wave there, and the beginning of the fashion industry. We caught it at this sort of pivotal moment.” On a Miami beach, they got approached by a woman called Nadine who worked for Click modelling agency in New York, who asked if Nick and Scott were brothers. They said yes, as Love recalls: “We created this lie on the spot, and she said, ‘Look, Bruce Weber, he's a big fashion photographer. He loves photographing brothers. He'd really like to meet you.’" The rest is history, as the ‘brothers’ went on to have a successful modelling career.

Despite this, after a few years Nick wanted to go to film school. “I told Scott and it definitely changed the dynamic, because we were known as brothers,” he says. “We had an amazing time. We went around the world. We made loads of money. We were fucking at it with everything that moved. But I could just sense that that was the end of it. And so for me, it was about going to film school, learning your trade, and getting out of it.”

Love found himself studying film at Bournemouth University in 1992, after lying about his qualifications to get in. “They couldn't check in those days, because it was all postal systems and stuff. And so I just got an interview and bullshitted my way in.” He originally got on a production course, having wanted to be a producer – and it seemed the course was set when, aged 24, Nick produced his first two films for Channel Four Films. “After one of the commissioning editors at the channel was a really cool woman called Kate, and she asked me if I wanted to produce a feature for them. She gave me a bunch of scripts to read, but I just didn't relate to them.” They were, for Nick, “a world that [he] knew nothing about,” and he told Kate as much. “She said to me ‘you fucking do better then.’ So I went off, and that's when I wrote what ended up becoming my first film, Goodbye Charlie Bright. She was actually really great in encouraging me to write about a world that I wanted to speak – it was about speaking to people from where I came from; proper south London social realism.”

How much did his earlier career in an image-obsessed industry impact his work? “Even films like Marching Powder, which are really grim in some respects and all about the gnarly side of life, still look good. They're all about the look. I think that probably comes from spending a lot of time with photographers who are very precise about what they find visually stimulating.”

Despite a catalogue of work that has made Love one of Britain's most prolific and best-loved directors, it was 2004's The Football Factory that would become a launch pad not only for him but a whole generation of men. “Two years after Charlie Bright I was selling Christmas trees to my mate in Chelsea every year,” he tells me. “The producers of The Football Factory came up to the Christmas tree stand with a script for it.” Loosely based on the 1997 novel of the same name by John King, it was originally started by another director before running into problems, to the point where “there was a half made version hanging around.” Knowing Love was a huge fan of the book (he had tried to buy the rights off King some years earlier), the producers offered him the chance to salvage the project. The film not only caused a stir among men – the media came out with pitchforks, highlighting its violent nature. Nick’s quick to counter this. “It's so much bigger than violence,” he says. “I think that was absolute bollocks – it's just about young men feeling disenfranchised and feeling like they want something to relate to. Do you know what I mean?" It’s a feeling that sounds familiar: twenty years on and you could be forgiven for thinking Love is talking about the disenfranchisement of men today. “That's why I mean it's bigger than that, because so few men can actually relate to this kind of hardcore fucking football violence.”

With it being a film that was speaking directly to its audience, was there ever a fear that the football hardcore would feel betrayed by the adaptation of football culture? "I’m a Millwall fan, and there was definitely some sense of having to try to get them on side, because making a film that's got Millwall in it without the hierarchy feeling okay about it could have been quite dangerous.”

Following the film’s release came the demand for Love's next project, which would be a remake of The Sweeney. "It was a dangerous thing for me to do a remake of a classic,” he recalls. “And it was actually very well received by the press and stuff, but it did no business at all. Completely bombed. Because it's hard releasing films in a cinema, and that’s the bottom line.” He’s had no such trouble with Marching Powder, which following a major campaign has done impressively well at the box office. “There was a sense of jubilation of actually making a few million quid. It’s so exciting because I'm used to the opposite really. You're only as good as your last success – it's awful really, that whole film business is like the NASDAQ or something."

The audience for Love’s latest work has interestingly been 18-25 year olds – he can do what so much of the media and so many brands can’t, which is speak directly to working class men. “There's obviously stuff in the papers at the moment about how the working class educational system is completely broken, and that it’s going to spawn a generation of men looking for elders to sort of guide them. I don't really want to sound like I don't know what I'm talking about, but for me it's more that I don't know what the fucking answers are. I just know that I'm a filmmaker that likes speaking to lads.”

There’s been a sense that the media are looking to Nick, much like they did upon the release of The Football Factory. “It's interesting because me and Danny were doing a tour for Marching Powder, and you can feel that people want to draw us into that kind of conversation. Do you know what I mean? Particularly with the far right and Andrew Tate – there's a whole sort of man's fear at the moment. The fucking irony of me is, I've made all these films and I spend two nights a week in fucking NA meetings talking about my feelings. I am bizarrely a pretty evolved man, and in a way that gives me legitimacy to make films about pretty unevolved men.”

Nick Love is without a doubt one of the film directors of his generation. But he might also be the director and voice for future generations at a time when leaders seem to be all but absent.