by Dylan Jones

).png)

It’s lunchtime, April 1996, and you are standing in the cavernous WHSmith near Ludgate Circus, not far from Holborn Viaduct. You arrived twenty minutes ago and are grazing the seemingly endless number of men’s magazines available for your delectation. There they all are, arranged like boxes of cereal or packets of washing powder in a supermarket, an array of titillation and infotainment that today appears to have piqued the interest of every man between the ages of 17 and 30 in the postcode. They, like you, are transfixed. They are, in no particular order: Esquire, Loaded, Maxim, Arena, FHM, Front, GQ, Eat Soup, Men’s Health – plus a myriad of other entry level titles. There you stand, in a mass of other men, six or seven deep – there are easily one hundred of you – flicking through the pages, smiling to yourself, sometimes laughing, before deciding which one to take back to your desk, probably with a pre-packaged sandwich and a fizzy drink.

It’s the mid-nineties, and buying magazines is something you do. Almost religiously. As you work nearby, in the service industry or the City, you’re probably wearing a pair of smartish suit trousers, a pair of sub-nosed hybrid shoes (they look a bit like formal office shoes but are basically fancy trainers), but your white (or possibly pale blue) shirt is untucked, because as this is the era of the New Lad, Britpop, and brash, tabloid television, no one tucks their shirts in any more. No way. In 1996, wearing an untucked shirt is tantamount to wearing love beads in the sixties, or perhaps a plastic dog collar or a pair of fluorescent socks in the teen-punk seventies – it’s a little bit of rebellion that proves you’re hip to the prevailing cultural winds. Not so hip you’re going to annoy anyone, but just enough. You’re obviously not wearing a tie, as ties seem to be the kind of things that models in fashion magazines wear. You no doubt bought the last Oasis single, you think bucket hats and flat-bottom check shirts are the personification of cool, and you buy magazines. A lot of them.

Because that’s what you do in 1996.

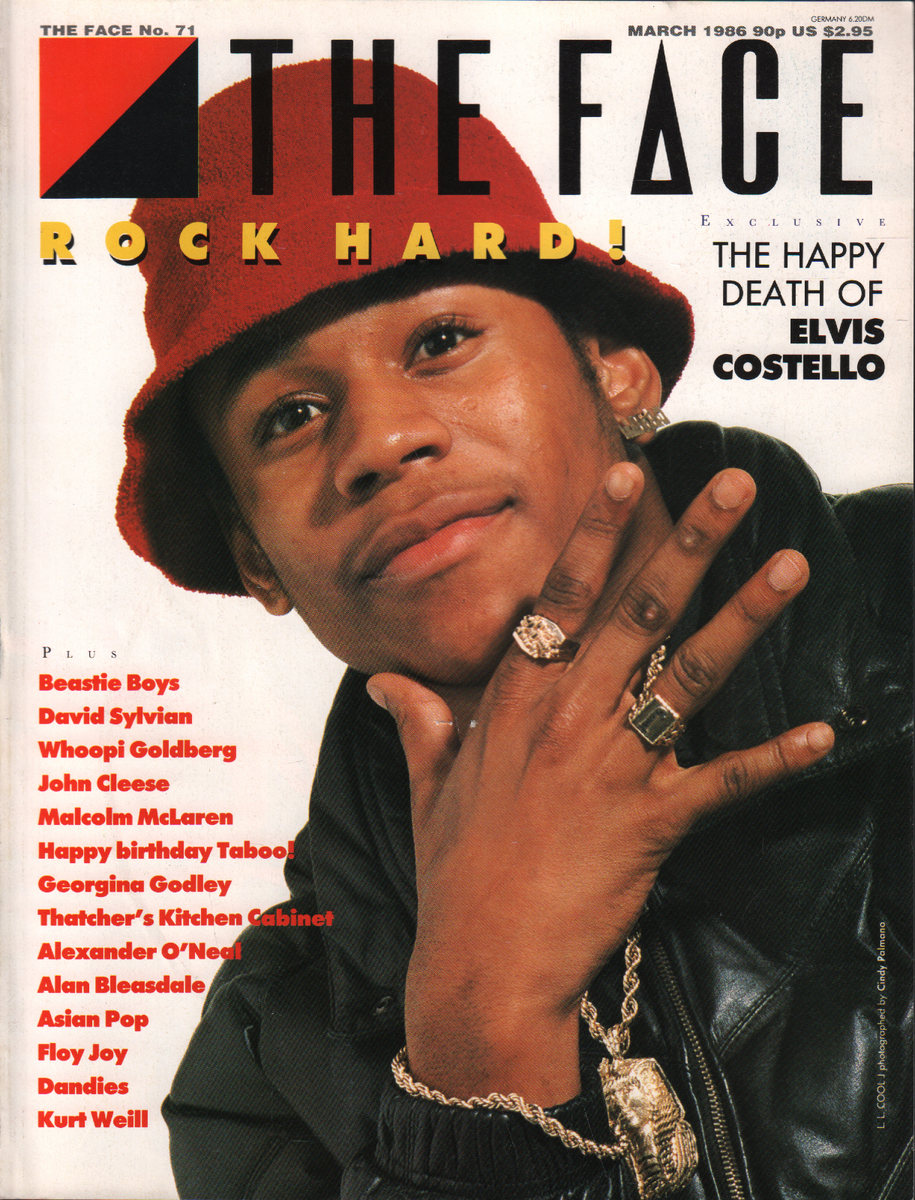

These men’s magazines were full of fashion, fancy furniture, smart journalism, interviews with film directors, and snarky titbits – these titles didn’t try and capture their audience, they basically turned up one day and said, almost in unison: Are you cool enough to buy us? Seriously, are you? This micro-genre was kick-started by ex-mod Nick Logan in 1986, six years after launching The Face, in an acknowledgement that young men were prepared to buy into a consumer lifestyle fuelled by luxury clothes, expensive beer, Italian interior design, and the occasional bit of glamorous sex (almost always photographed in blurry black and white).

The eighties was the decade that put the arch into postmodern architecture; the decade of the oversized car phone, the overpriced mountain bike, the over-marketed compact disc, the over-stuffed Filofax, and supercharged power dressing for men. Men in the eighties tended to want to look like merchant bankers, aspiring to a world of tall buildings, tall women and tall stories.

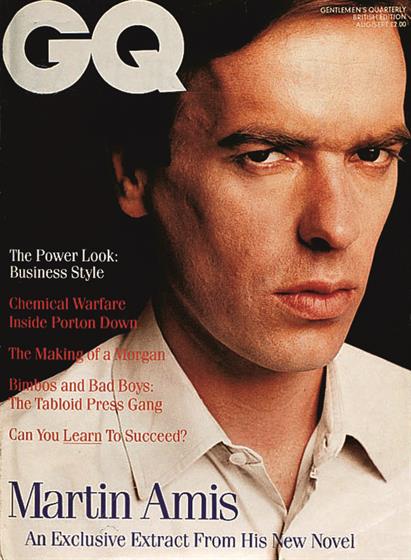

Condé Nast's GQ was launched to reflect the aspirations of a generation who assumed a designer lifestyle was their birthright; a lifestyle that – for a while – was defined by men’s magazines. It was in men’s magazines where you would find the taste that you espoused in public; where you could live your dreams – even if you knew they were never going to be realised. Here, on these beautifully printed glossy pages you would find the matte-black dream home. ‘Designer’ became the prefix du jour, while design was everything, and everything was design.

The GQ generation appeared to have ambition and self-fulfilment hardwired into it from the get-go, and its readers seemed to like it that way. They willingly embraced the exercise book as the body beautiful became a male ideal. And they started to become educated consumers – in fact consuming more like women (the most sophisticated consumers of all). Some tried to label us ‘New Men’, although I'm not sure we were ever that sophisticated. This new consumer rose to prominence during a decade where reinvention was almost a necessity rather than a pipedream; an exotic creature who apparently was as happy washing up as he was changing a nappy. Essentially, he was an invention – although an invention exploited mercilessly by the luxury goods industry. The consumer was real, but perhaps not his bankroll.

This affected magazines in a huge way.

“The biggest button these magazines had to push was the one marked ‘Sex’.”

Of course, sex was the principal lever that turned a small bunch of esoteric men’s magazines into the tsunami of publishing activity which enveloped the nineties.

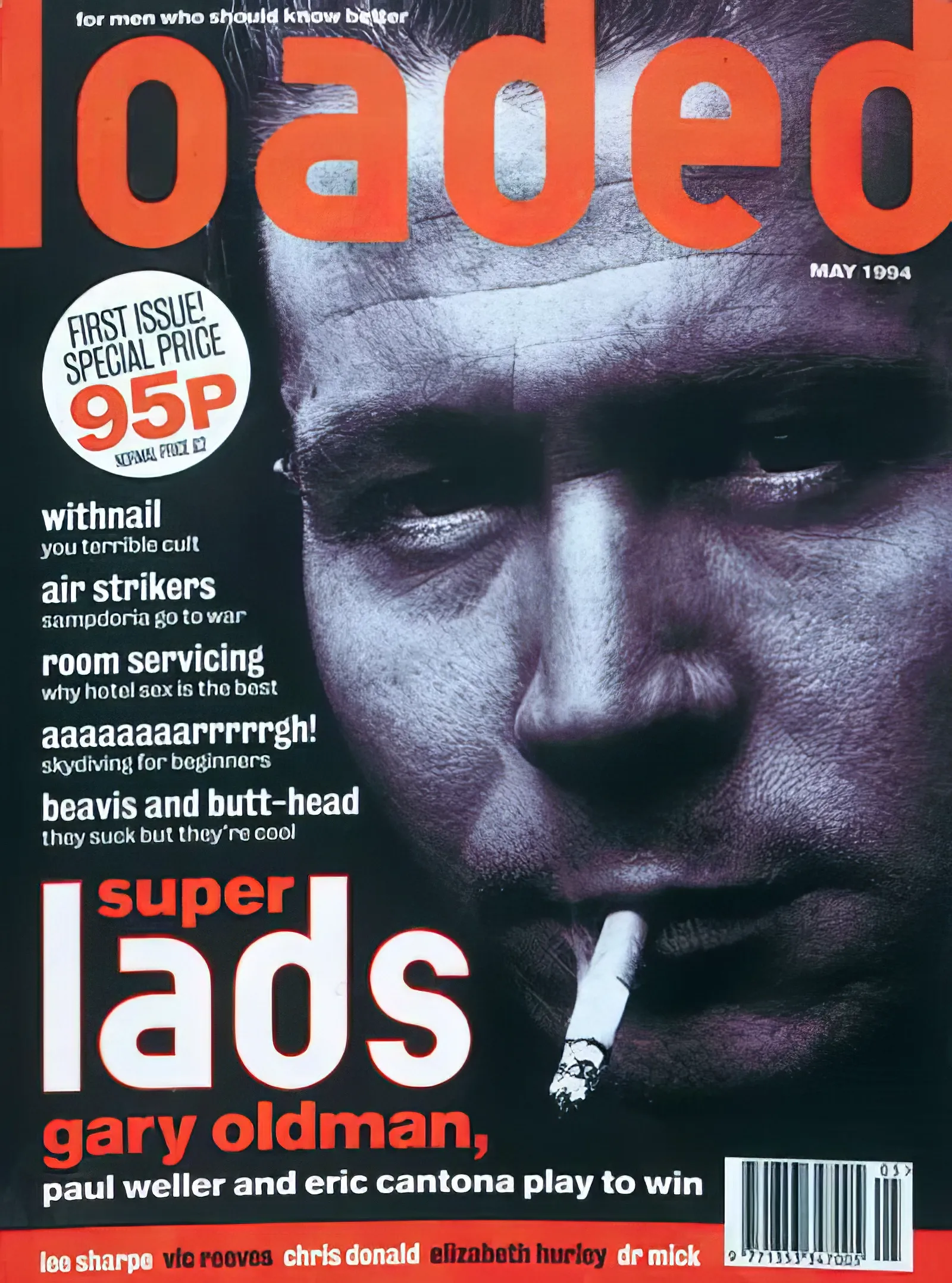

When James Brown launched Loaded for publishing behemoths IPC in 1993, he was deliberately targeting a generation of men who would have been intimidated by the likes of GQ and Arena.

He was speaking to a generation who knew they couldn’t afford the good life, but who were more than happy with a diet of football, pop music, and – increasingly – a legitimisation of sex.

As long as you put inverted commas around your insult, it was acceptable.”

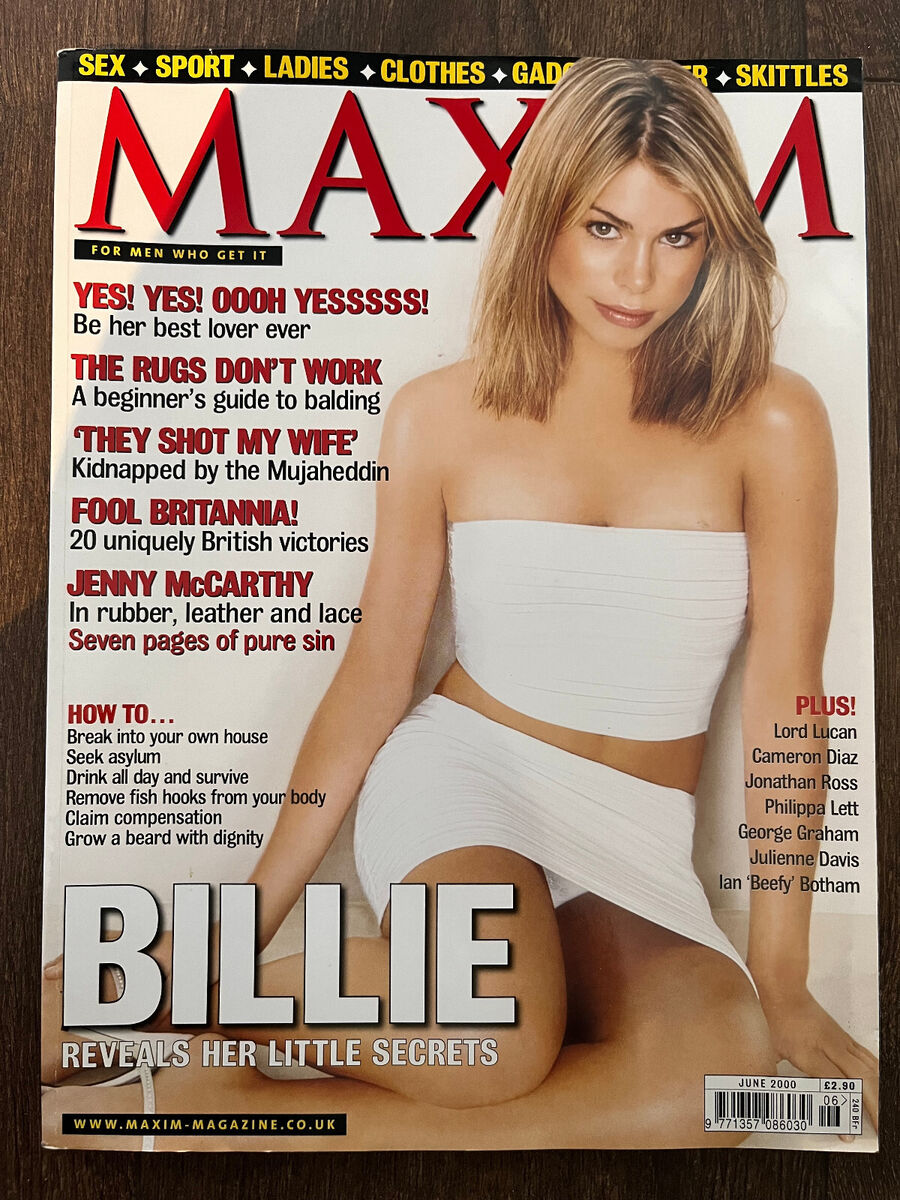

The cool irony of the eighties was immediately replaced by the tabloid irony of the nineties. For a while you could perform most acts of linguistic, sartorial, or musical interpretation as long as you did whatever it was within the confines of irony. As long as you put inverted commas around your insult, it was acceptable. Hence the way in which the new generation of men’s magazines – Loaded, FHM, Maxim etc – became bastions of deliberately ironic soft-core porn.

To look at the dozens of men’s magazines that launched in the nineties, you could have been forgiven for thinking that the Alpha Male had – perhaps unwittingly, perhaps wittingly – had some sort of frontal lobotomy. Apparently, you couldn’t be a man unless everything you consumed, everything you appreciated, everything you read, watched, and listened to came complete with its own inverted commas. Big yellow foam inverted commas that proved you didn’t take things too seriously.

The world of culture was opening up in such an egalitarian way that in many respects they didn’t have to move very far to meet it; this wasn’t so much cultural emancipation as a mass market revolution. Who knew that being ordinary could be so cool, or, more importantly, so acceptable? This was a new world of the ostensible and the average. It felt temporary but it also felt like a lot of fun. What a laugh to put off growing up until you really couldn’t put it off anymore?!

If anything exemplified this new generation it was nightlife. In the late seventies and early eighties there were strict demarcation lines about nightclubs; they were innately exclusive, available only to those in the know, those on the guest list, or those in the press. By the early nineties, nightlife was resolutely inclusive, driven in part by the acid house explosion. If, in the early eighties, we were dancing to imported funk in extremely small rooms in Soho; by the mid-nineties, we were throwing shapes to an industrial noise in fields the size of stadiums, in parts of the countryside that had never even seen a velvet rope. Suddenly it was much easier to be fashionable, especially if you were a young man. You even had a raft of new magazines aimed at you. Could you believe that? They even had sex in them. Loads of it!

The likes of Esquire and GQ, meanwhile, were pretty steadfast, largely keeping their heads above the murky waters of this new publishing boom; continuing to produce the same top-end journalism and slick fashion pages they had been producing since the back end of the eighties.

But by the end of the nineties even GQ had ended up putting women on its front cover.

The men’s magazine boom ended with a whimper rather than a bang (fnaar, fnaar). Inevitably, the mighty FHM (which had been selling over a million copies a month) started to take a dip in circulation, and then the rest followed suit. Obviously, publishers panicked and wondered what the hell they could do.

The biggest button these magazines had to push was the one marked ‘Sex’ – meaning that even the slightly more sophisticated titles started to amplify their sexuality in an increasingly vulgar way. This of course started to cross a line, as many magazines would start to verge on pornography, which, when combined with the rise of the internet – where sex was available at the flick of a switch – soon contributed to their demise. There was a brief a flurry of activity from some of the major publishers with the weekly titles Nuts and Zoo, but while initially they reinvigorated the market, they too were soon gone. The young men became older men, and advertisers started to shrug. When all the sex was gone, the market retrenched to where it had been before: a smaller landscape dotted with the likes of GQ (eventually the market leader), Esquire, and Men’s Health. Soon, rather than trying to squeeze upmarket totty onto the page, any kind of libido was banished, almost as though it hadn’t been there in the first place. The monthly men’s magazine market found itself neutered, at a loss as how to define itself. Advertisers still liked the idea of a tightly targeted upscale audience, but even this was drifting online.

Nowadays, newsagents feel very different to how they did thirty years ago. Many have closed, and you’re never going to see a hundred men at lunchtime deciding which magazine to take back to their desks. Community has given way to the isolation of the phone, where lifestyle and all its trappings coalesce with no particular place to go.

And 1996 seems as far away from the present as 1966 did then. In fact, as I remember it – and I remember it well – 1966 felt an awful lot closer.